The ineptitude in the handling of the

employment of young doctors in the medical service is mind-boggling. The

healthcare system is collapsing in the face of the pandemic. Healthcare workers

are being strained to the limit of their capacity. The daily count of

infections and deaths does not put a number on the efforts of these valiant

workers. Now, eighteen months into the pandemic, there is still no visible

signs of when the pandemic will be brought under control. Instead, a danger looms

of the system itself failing. Against this background, instead of treating the

additional numbers of qualified doctors as a boon to the health system and the

nation as a whole, decision-makers are embroiled in an unnecessary controversy

about the tenure of these young doctors and their future careers. If matters

are not quickly resolved the situation would alienate a whole generation of

doctors and stifle their enthusiasm and motivations.

This country needs more doctors regardless

of the doctor to population figure standing at 1:454 (2020). With a dispersed

population and many living in rural areas, the WHO ideal of 1:400 does not say

anything about whether public healthcare reaches those in remote and fringe

areas. The ideal figures also say nothing about how these ‘ideal’ figures will cater

for extraordinary situations like those created by a pandemic like that being

experienced now. Total Covid-19 cases from March last year exceed 900 thousand.

New positive cases reported daily exceed 10 thousand patients. The system is

under great strain, not least because of the shortage of doctors. A sufficient

number of skilled and motivated health workers is critical to the performance

of any health system, particularly now in the COVID‑19 pandemic. Faced with similar situations, other countries,

including OECD countries, have cut the bureaucratic red tape to press doctors

who are outside formal systems into service to fight the pandemic.

Unfortunately, very often in this country, official

decisions on important social matters as those now concerning the employment of

doctors in the public service are often influenced by issues of race, religion,

and political expedience. In the present case, an additional, widely held reason

preventing a rational decision is that the doctors graduated from private

universities. This is not based on the quality of their education but simply

that they are the products of ‘money-making’ enterprises. For that reason alone,

it is being proposed by some that the numbers qualifying from private institutions

must be reduced in the future to prevent similar future predicaments. This is

an untenable argument which, the sooner it is put to rest the better.

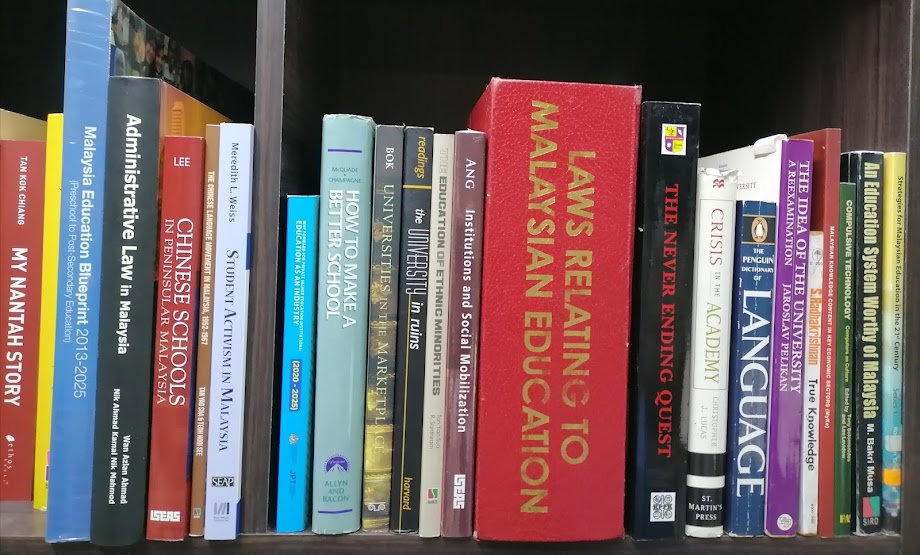

Private universities, including those with

medical schools are the product of an evolution that was shaped by the

unfulfilled demand for higher education. A large section of our population, at a critical moment in their lives, would not have had the opportunities for

further education after school but for the offerings of private colleges. From

around the 1980s, long before the law allowed the creation of private

universities, private colleges in this country changed the very nature of

higher education as traditionally defined to make it more accessible to

learners. The innovations private colleges introduced (too many to repeat in

this article), separated the substance of higher education from the physical

trappings of the university and allowed a university-level education to be

delivered outside the lecture rooms and even outside the country of its

location. What followed was a historical transformation that democratized

higher education and brought it within the reach of our school-leaving youth

even as their growing numbers found them no place in local public institutions.

The private sector of higher education in

this country must be respected for its contribution to higher education. Many

of the owners of these private institutions are there not just to make money.

They set up colleges and universities out of a commitment to providing

education and with philanthropic motives. The development of the private sector

of higher education, which now hosts more than half the tertiary education

population in this country, no doubt, also played an important role in stilling

potential social disquiet that would have arisen because of the unmet demand for

higher education. Reviewing the sector in 2008, the EPU report entitled, Strengthening Private Education Services in

Malaysia, 2009, described the private education landscape then as;

‘. . . a thriving

sector widely recognized in international academic circles as one of the most

innovative and progressive in the region. Education experts and investors

consulted during the course of this project have highlighted Malaysia as one of

the most “open” regimes and more “attractive” markets in Asia. Among its

achievements are;

Split-degrees and

international transfer programs, particularly the proliferation of ‘twinning’

programs with premier international institutions are often heralded as some

of the innovations introduced by the private education entrepreneurs; Malaysia

is the 10th largest exporter of education, catering to 80,000 foreign students

or 2% of the global market share.

Most of the achievements reported by EPU

were realized before the passing of the Private Higher Educational Institutions

Act in 1996 (Act 555). The far-reaching policy changes implemented by the Act set

the pace for the next big leap in the development of the private sector. The Act

legitimized private education and assigned it an equal role with that of public

institutions. It allowed, for the first time in the country’s history, for private

universities to be established. The significance of that move was the government’s

relinquishment of its long-held monopoly over universities. Because of this bold

step and other reasons, Act 555 radically altered the landscape of higher

education. The provisions on private universities also allowed foreign universities

to set up branch campuses in this country. As a result of these changes the private

sector of higher education today is so diverse that it represents all the main

systems of the English-speaking world. The same factors that attracted foreign

universities also attracted foreign students in large numbers into local

universities and colleges. The stimulus for these radical developments was the

presence in 1996 of a mature, locally developed, private higher education

system that was recognized internationally. It was a system that was well

prepared to build on the opportunities created by Act 555.

The private sector of higher education is

subject to tight control by different regulatory authorities established by Act

555 and other legislation. An important part of the regulatory system is the

accreditation of the courses which is by statute vested in an independent

agency – the Malaysian Accreditation Agency (MQA). Under the MQA Act, medical

and other professional qualifications can only be accredited with the approval

of the related professional body. In fact, the relevant provisions of the MQA

Act 2007 gives the MMA and the medical profession a greater say on accreditation

than the Agency itself.

Many of the doctors at the heart of the

present controversy would be graduates of the private medical schools

established under the regime of Act 555. The predicament they face is not of

their making but that of a failure by the Health Ministry to anticipate the

increased output of doctors from the private sector. The doctors from private

medical schools are entitled to the same treatment as their counterparts from public medical schools. Their absorption into the medical health service on traditionally

established terms should not be delayed any further.

One final point. The first medical school

in this country, the King Edward VII College of Medicine was established in

1905 only because of the persistence and funding provided by philanthropic businessmen

of that era. Malaysia’s first university, Universiti Malaya now claims its

ancestry to that institution.